Symptoms of a dysfunctional team

A lot of teams don't operate well. Learn how to spot them and you'll have a more rewarding career.

Posted , 7 minute read.(image credit: rawpixel)

I've had a lot of jobs (8 since 2012), which means I've worked with a lot of teams. One of the main reasons I changed jobs so frequently for a couple years is that many of the teams I joined felt very dysfunctional—it was difficult to get work done and there wasn't a clear sense of purpose.

Hopefully, my cheat sheet of questions for your interviewer will help you identify dysfunctional environments during the interview process, but when you're early in your career it's hard to tell whether your team is functioning as it should. There are some symptoms that I've found to indicate that a team has major cultural or technical issues that cause it to be dysfunctional.

Overtime assumed

The biggest indicator is when it becomes assumed that you'll regularly work beyond the 40 hours a week for which you're paid. Software development positions are notorious for a culture of overwork and burnout. In most professions, the federal Fair Labor Standards Act requires that overtime is paid at 1.5x your hourly rate, with salaried positions considered "exempt." However, the FLSA specifically exempts all computer professionals from overtime pay, which laid the groundwork for burnout culture to flourish.

Overtime means that too much work has been planned for too little time. It's generally understood that overtime has a detrimental effect on productivity. A synthesis of studies from 2004 evaluating productivity in construction projects has clear figures showing the drop in productivity. There are potential benefits to brief "crunches" of 1-2 weeks of 50 hours of work, but beyond that and the drop in productivity outweighs the additional time worked. That's right: studies show that those working 60+ hour weeks accomplish less than people working 40.

Long feedback cycles

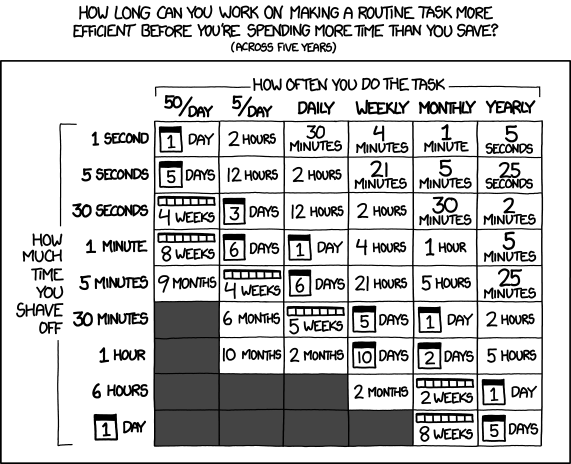

One of the biggest drains of productivity is long feedback cycles. When you change a line of code, how long do you have to wait before you can tell if it worked? With modern tools and languages, cycle time should be measured in tens of seconds, if not less, but what you can expect depends on the domain you work in. Reducing small amounts of wasted time in repetitive tasks adds up, especially when they're done frequently. As always, there's a relevant XKCD:

If it takes multiple minutes to run a development build, consider how many hours your team spends collectively sitting idle. Outside of build times, some of this optimization is up to you as a developer; is there a way for you to short-circuit directly to the code path you're testing? If it takes you 10 seconds to click through UI or input data, that can quickly add up to hours of burned time over weeks of development. Modifying the surrounding code to remove these manual steps can have a significant impact on how quickly you can work.

A major contributing factor to long build times is how familiar your team is with the tools they use.

Lack of expertise with tools used

If a tool has been misconfigured, is being used without optimization, or solves a different problem than what your team has, the length of the feedback cycle is often the most visible indicator that something is wrong. Build times (both in development and when deploying to production) and the time needed to configure a local development environment are excellent proxies for your team's overall level of expertise with their tools as well.

One of the most common reasons behind a team lacking expertise with their tools is when they've followed trends, rather than addressed the problems they encounter. Frontend and Javascript developers are often criticized for this behavior, but I've seen it in backend and ops as well—big data, serverless, AI, Docker, microservices. These are useful, innovative new tools, but using cutting-edge tools that you don't understand is worse than simpler infrastructure you're more familiar with.

It's hard to judge whether the team understands a tool if you yourself don't, but you can clarify what problems a tool is meant to solve by talking with others. Within your team, there should be a clear answer for why the tool is used and why it was picked over alternatives. Talking with others outside the team, like at a conference, meetup, or online, you may find that you don't have the problems that a tool is designed to solve.

Poorly configured tools also contribute to another major symptom: outages.

Frequent outages

Outages should be a rare event, happening only after an external incident or a confluence of factors. In a healthy environment, outages are followed by postmortem that ends with process or infrastructure changes to prevent the same incident from recurring. A prerequisite of an effective postmortem, however, is a deep understanding of what went wrong and what changes are possible. Shallow knowledge of your tools limits both of these. If an outage was resolved by turning it off and back on again, the opportunity to learn from it is usually lost.

Outages generally come in a few different flavors. They could be caused by performance problems, failed deployments, or If your team has a long cycle time, it becomes prohibitively time-consuming to polish off the small bugs at the end of a unit of work. These bugs accumulate, eventually leading to a crash in production or an invalid deployment. Worse yet, these same issues impair your ability to get the service up and running again. It's a cycle that feeds itself, and teams or companies that are not able to address the fundamental issues may end up spiraling to their death.

Excessively rigid process

Especially as you gain expertise and advance in your career, you need to have a certain degree of flexibility in completing your work. Prioritization will never be perfect and you'll always find issues in the code you touch. It's rare that invisible concerns like performance, maintainability, and supporting infrastructure bubble to the top of a product manager's priorities. Well-operated organizations will typically have engineering leadership to balance this tension, but often it falls to you, an individual developer.

A restrictive process may be a knee-jerk response put in place after features were repeatedly delayed (often due to long cycle times) or frequent outages. If developers don't balance features and internal work, the process may be a way to force features to be prioritized. The process may also be a band-aid over fragile build tools as well—"just follow the process to the T and it'll all be okay."

It's also a symptom of problems within the leadership. Rigid process and micromanagement might be due to inexperienced managers, or those self-conscious about their level of contribution.

Leadership without obvious contributions

It should be apparent what role the leaders of your team play when you look for it. A project manager should facilitate the creation and prioritization of tasks, making sure they contain the information you need to complete it. A tech lead should ensure that the process and tools being used enable you to ship code quickly and without error. A product manager should verify that what's being built meets the end-users' needs. It may not be obvious from where you sit, depending on your role within the team, but each of these individuals should be furthering the team's goals in their own way.

If, when talking to coworkers and those above you in the organization, nobody can quite articulate what it is the people leading a team are contributing, the team has a major leadership problem. When those in charge of decisions abdicate their responsibilities, the process and technology begin to break down. Over time, the project may become mired in tech debt, waste people's time as they track down information, or ship features that nobody uses.

Often, these types of leaders are struggling within their defined role. Unfortunately, a relatively common form of this manifests as bad success metrics for the team as a whole.

Organizational metrics unrelated to outcomes

Objects and Key Results (OKRs) and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are two buzzwords that became popular after the publication of books of the same name. The ideas behind them are excellent: organizations should measure that their efforts are working. However, if these OKRs or KPIs don't relate to positive outcomes for the team or organization, then they're simply irrelevant numbers being used to micromanage developers.

Unfortunately, this is often out of your control as an individual contributor. It may even be out of your purview, and they may be locked in for the quarter or even for the year. Misalignment between key metrics and actual, useful software is a major problem for the organization.

Responding to these problems

These problems happen at companies of all sizes and are often deeply rooted in the culture that a team has grown around. There aren't one-size-fits-all solutions to these problems, and recognizing dysfunction isn't enough to fix it. Ultimately, many of the solutions to these problems require either buy-in or changes from management, which can be hard to effect when you're a few rungs down from them.

One important thing to keep in mind is that individual contributors are usually first to feel the effects of these breakdowns. At an otherwise healthy company, those in charge may know that something is wrong, but not have the information they need to diagnose the problem. If any of these resonate with you, they would make good conversations to have during a one-on-one with your manager.

If an organization is unable or unwilling to change, it may be a sign to freshen up your resume and begin exploring your options. It's easy to mistake the problems of one team with problems that are organization-wide, though. If you encounter problems like these, talk with coworkers on other teams about their experience. They may be able to help you resolve them, or you might be able to move within the company.

Thanks for reading! I'm on Twitter as @vcarl_ (but most other places I'm vcarl). I moderate Reactiflux, a chatroom for React developers (check out #jobs-advice!) and Nodeiflux, a chatroom for Node.JS developers. If you have any questions or suggestions, reach out!